October is ADHD Awareness Month — an opportunity to look beyond observable symptoms and explore the molecular architecture behind the condition.

ADHD affects roughly 350 million people worldwide, with an estimated heritability of 70–80% in childhood, among the highest of any psychiatric disorder.

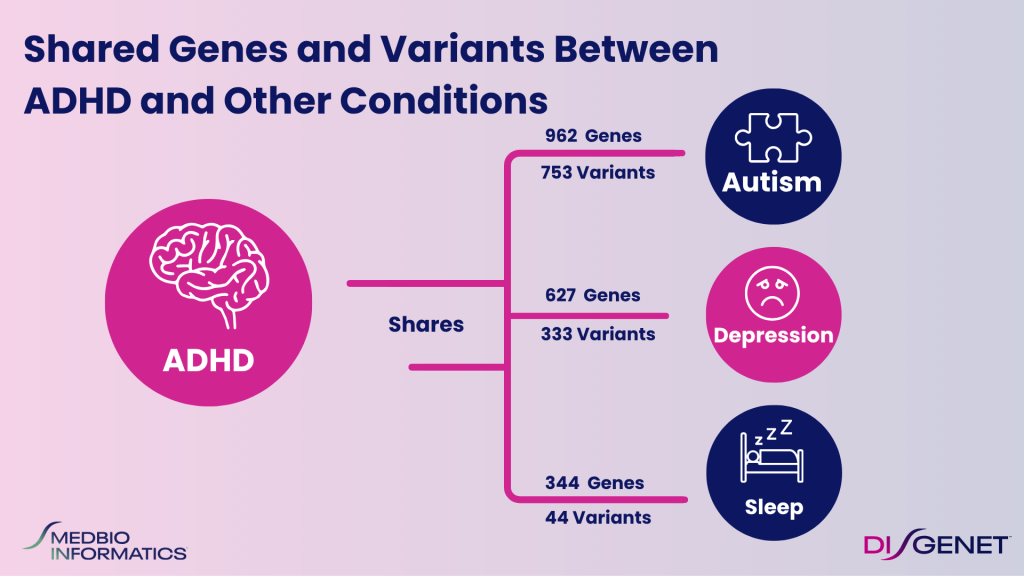

Yet it rarely occurs in isolation. Studies into ADHD genetics reveal that many of the same genetic signals influencing ADHD also contribute to autism, depression, anxiety, and sleep regulation.

Large-scale meta-analyses from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) and iPSYCH cohorts have identified more than 80 loci associated with ADHD risk, with significant overlap across neurodevelopmental and mood disorders.

This shared genetic architecture shows that single genes can influence multiple psychiatric outcomes. Understanding these links is essential for next-generation therapeutic strategies.

From Single Variants to Polygenic Risk

Historically, ADHD genetics focused on candidate genes such as DRD4, SLC6A3, and SNAP25.

Today, Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) capture the cumulative effect of hundreds of variants, revealing subtle contributions missed by single-gene studies. PRS models have demonstrated potential for identifying individuals at higher risk of early-onset ADHD, educational challenges, or treatment resistance.

DISGENET supports this shift from single-gene analysis to polygenic, systems-level research.

By integrating variants, genes, and phenotypes, DISGENET helps pharma, biotech and clinical genomics researchers:

- Identify ADHD-associated variants across multiple datasets

- Examine shared genetic risk across ADHD and comorbid disorders

- Map gene sets to molecular pathways and functional annotations

- Highlight pleiotropic genes and cross-disease associations

- Explore gene–drug–disease relationships and candidate biomarkers

- Build network-level models to study biological convergence and prioritize research hypotheses

ADHD and Its Molecular Network

ADHD overlaps with other conditions at the genetic level:

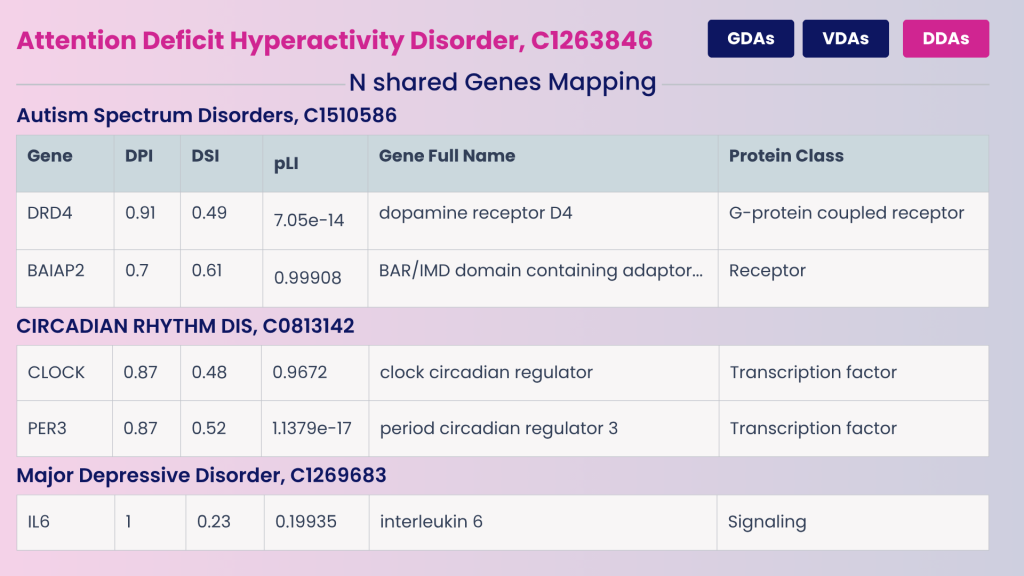

- DRD4 and BAIAP2: ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorders

- CLOCK and PER3: ADHD and circadian rhythm dysregulation

- IL6: ADHD and depression

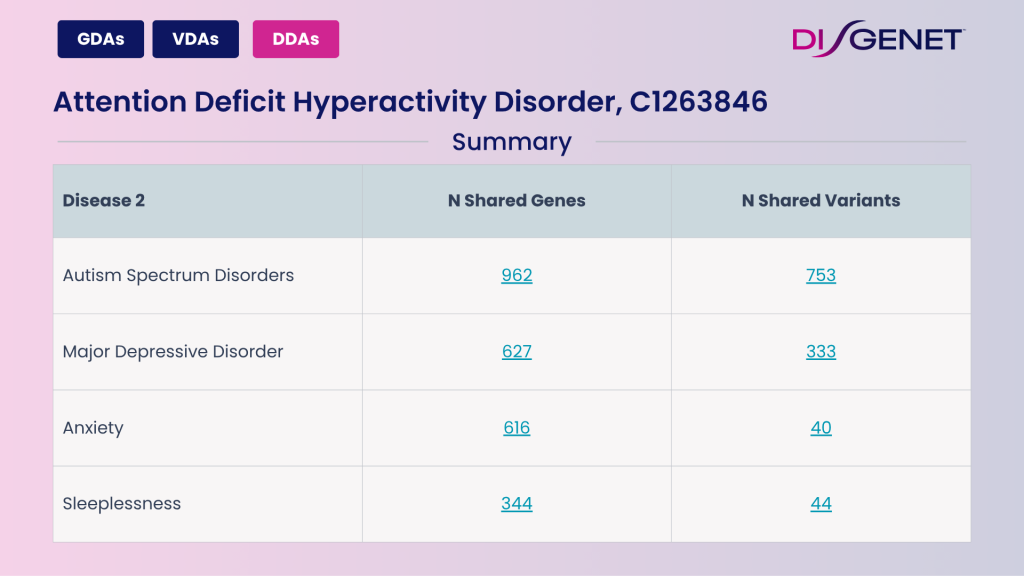

Explore Comorbidities in DISGENET

Example of shared genes between ADHD and some of its comorbidities. Each gene is annotated with metrics that help interpret its role across diseases:

- Disease Pleiotropy Index (DPI) reflects how broadly a gene contributes to multiple disease classes

- Disease Specificity Index (DSI) indicates its relevance to ADHD specifically

- pLI (probability of loss-of-function intolerance) captures functional constraint

- Protein Class provides information about its role

Recent DISGENET updates make these Disease–Disease Associations (DDAs) actionable, highlighting which genes and variants are shared, their biological relevance, and pleiotropic potential. This enables you to move from simple associations to testable hypotheses, pinpointing cross-disease targets and candidate biomarkers for precision research.

Learn more about the latest Disease–Disease Association updates in DISGENET here

Precision Psychiatry in Action

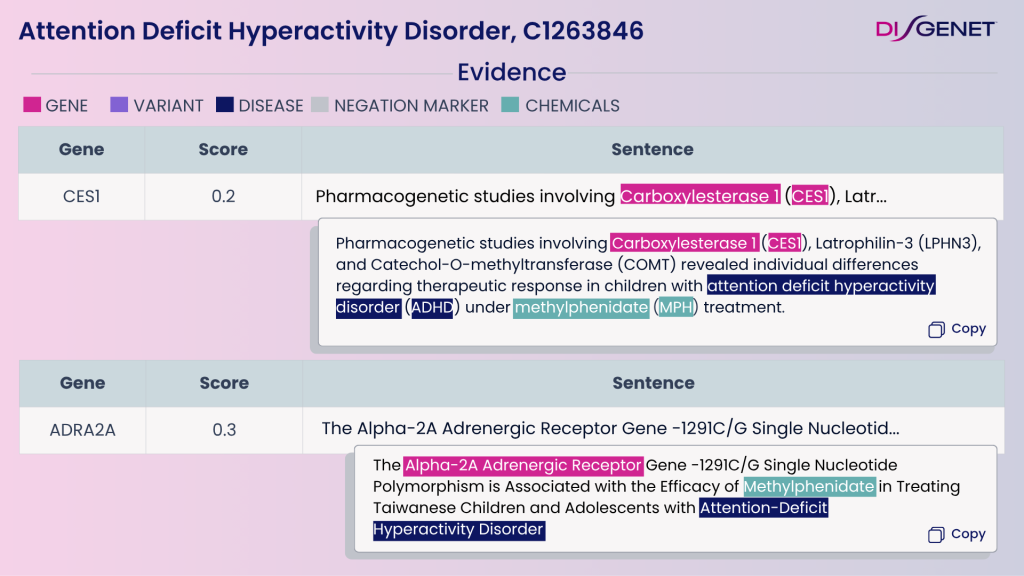

Genetics and pharmacogenomics are reshaping ADHD treatment.

Medications like methylphenidate, atomoxetine, and guanfacine target dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems, yet treatment response varies widely.

Variants in CES1, CYP2D6, and ADRA2A influence drug metabolism and efficacy.

DISGENET’s pharmacogenomic annotations provide:

- Gene–drug–disease relationships relevant to ADHD

- Insights into mechanisms driving differential drug response

- Potential biomarkers to distinguish responders vs. non-responders

Toward a Systems-Level Understanding

ADHD is increasingly seen as a spectrum of interconnected molecular and clinical profiles. By combining genetics, comorbidities, and pharmacogenomic data,

DISGENET empowers research teams to:

- Build network-level models of ADHD

- Identify shared mechanisms with related conditions

- Advance personalized strategies for prevention and treatment

ADHD Awareness Month 2025 reminds us: attention is not just psychological — it’s molecular, polygenic, and deeply connected.